INTRODUCTION

Although spinal subdural hematoma (SDH) is rare, the incidence has increased significantly in the era of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)4,10). Predisposing factors for spinal SDH include trauma, coagulopathy, vascular malformation, iatrogenic maneuvers such as lumbar puncture, tumor bleeding, alcohol abuse, and spontaneity3,4,8,13). Spinal SDH reportedly comprises only 6.5% of all spinal hematoma8). Spontaneous spinal SDH associated with cranial SDH is extremely rare1). We describe a case of spontaneous concurrent spinal and cranial SDH, in which spinal SDH was detected one day prior to a cranial lesion.

CASE REPORT

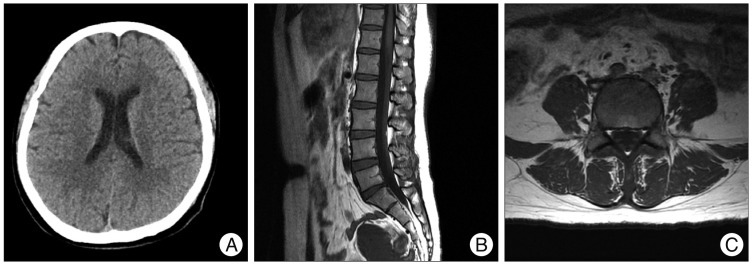

A 39-year-old female presented with about a 10-days history of low back pain and pain radiating from both legs. She was transferred to our department under the diagnosis of spinal SDH. The patient had no history of antecedent head or back injuries, but had intermittent pulsatile headache for 2 weeks. Laboratory examinations eliminated the possibility of coagulopathy-related diseases. Neurologic examination showed no definite motor weakness and sensory change. Spinal MRI showed a diffuse mass encircling the thecal sac, leading to moderate to severe central spinal stenosis at the L4 to S2 vertebral levels. Axial MRI revealed that the hematoma was located between the epidural fat and cerebrospinal fluid space, indicating localization in the subdural space (Fig. 1).

The patient was treated conservatively because the pain was not severe. She refused surgery. One day after admission, the pre-existing headache (which had not been a complaint in the outpatient clinic) became aggravated, and nausea and vomiting developed. Computed tomography of the brain revealed a chronic cranial SDH associated with midline shift in the left hemisphere (Fig. 2). The cranial SDH was evacuated, which prevented brain herniation if lumbar decompression was necessary. Postoperatively, the headache gradually resolved (Fig. 3A). We scheduled another evacuation of spinal SDH to be performed if neurologic deficit developed. However, low back pain and pain radiating from both legs gradually improved. Three months later, a lumbar MRI showed complete resolution of the spinal SDH (Fig. 3B, C).

DISCUSSION

Simultaneous spinal and intracranial SDHs are relatively rare, having been reported in only 18 cases7). Furthermore, spontaneous spinal SDH concurrent with cranial SDH is extremely rare, reported in only three patients to our knowledge; none had a history of trauma or surgical procedures. However, three patients had some medical history of anti-platelet therapy, aplastic anemia, or tumor metastasis6,10,17). In our case, there was no history of trauma or any invasive procedure. The cranial lesion was detected after the detection of spinal lesion.

The mechanism for simultaneous development of both spinal and cranial SDHs is unclear. Spinal hematoma may be caused by a rupture in the spinal vessels5,9,13). However, there is a lack of bridging veins as a source of spinal SDH in the spinal subdural space compared with the cranial counterpart9). Therefore, the incidence of spinal SDH is significantly lower than that of cranial SDH. Redistribution of cranial SDH to the spine might be a cause of spinal SDH10,15,17). Spontaneous rapid resolution of acute cranial SDH has been documented in some cases2,14). Unlike acute SDH, chronic SDH has an inner and outer membrane. Enlargement of hematoma caused by rebleeding might rupture the membranes, leading to redistribution of the hematoma to the spine, most likely resulting from gravity. In almost all previously reported cases of concomitant cranial and spinal SDH, the spinal SDH was located below the lower thoracic spine6).

In the present case, the patient had no recollection of traumatic or iatrogenic history causing the concomitant hematomas. However, a seemingly trivial trauma might have been forgotten. Trauma is also important in the development of concomitant hematomas7). In addition, concomitant intracranial and spinal SDHs can develop in patients with intracranial hypotension caused by ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement 12,16). Low cerebrospinal fluid pressure decreases the subarachnoid space, leading to widening of the subdural space, which facilitates the migration of a hematoma and tearing of bridging veins.

Spinal SDH is rare compared with the cranial counterpart. However, it may be a potential sequela of cranial SDH by migration or redistribution. As in the present case, a patient with spinal SDH may complain of headache, nausea, and vomiting derived from the brain lesion. Therefore, the incidence of spinal SDH concurrent with cranial SDH could be underestimated11). Spinal SDH can be treated by conservative therapy or surgical decompression7). Patients with progressive neurological symptoms should be treated with surgical intervention. The present case suggests that a patient with spinal SDH, especially without direct trauma history, should be evaluated to check the possibility of spinal lesion accompanied by cranial lesion. The evacuation of the spinal SDH may lead to the development of tentorial herniation in patients with concomitant cranial SDH.

CONCLUSION

A rare case of spontaneous spinal SDH concurrent with cranial SDH is reported. The causes of the non-traumatic spinal SDH should include brain origin. Spontaneous complete resolution of the spinal SDH was presently observed. However, surgery should be indicated for patients with neurological deterioration.