The Comparative Morphometric Study of the Posterior Cranial Fossa : What Is Effective Approaches to the Treatment of Chiari Malformation Type 1?

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to investigate changes in the posterior cranial fossa in patients with symptomatic Chiari malformation type I (CMI) compared to a control group.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed clinical and radiological data from 12 symptomatic patients with CMI and 24 healthy control subjects. The structures of the brain and skull base were investigated using magnetic resonance imaging.

Results

The length of the clivus had significantly decreased in the CMI group than in the control group (p=0.000). The angle between the clivus and the McRae line (p<0.024), as the angle between the supraocciput and the McRae line (p<0.021), and the angle between the tentorium and a line connecting the internal occipital protuberance to the opisthion (p<0.009) were significantly larger in the CMI group than in the control group. The mean vertical length of the cerebellar hemisphere (p<0.003) and the mean length of the coronal and sagittal superoinferior aspects of the cerebellum (p<0.05) were longer in the CMI group than in the control group, while the mean length of the axial anteroposterior aspect of the cerebellum (p<0.001) was significantly shorter in the CMI group relative to control subjects.

Conclusion

We elucidate the transformation of the posterior cranial fossa into the narrow funnel shape. The sufficient cephalocaudal extension of the craniectomy of the posterior cranial fossa has more decompression effect than other type extension of the craniectomy in CMI patients.

INTRODUCTION

Chiari malformation type I (CMI) is characterized by caudal displacement of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum and into the cervical canal28). Chronic tonsillar herniation develops in several etiopathogenic conditions such as global cranial construction associated with multiple craniosynostosis, achondroplasia, cranial settling, and cerebellar ptosis associated with hereditary disorders of the connective tissue23). Recent studies have shown that chronic cerebellar tonsillar herniation (CTH) occurring in CMI primarily results from a paraxial mesodermal defect that leads to underdevelopment of the occipital bone and overcrowding of a normally developing hindbrain within a primary, small, and shallow posterior cranial fossa because of an anomaly in the embryological development of the occipital bone1,19,22,23,25,27,29). However, the exact pathogenesis of posterior cranial fossa associated with CMI has not yet been clarified.

The main treatment of CMI is to enlarge the foramen magnum and expand the dura by surgical approaches, such as a simple suboccipital craniectomy, craniectomy with C1, C2 laminectomy, duroplasty. However, the most appropriate surgical technique is controversial, because the pathophysiology of CMI is not well known26). Therefore, we studied the morphometry of posterior cranial fossa in patients with symptomatic CMI and clarify what is the most effective, ideal surgical technique based on the morphological changes of CMI patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical evaluation

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical and radiological data for 12 symptomatic patients (4 males and 8 females) with CMI and 24 healthy control (10 males and 14 females) subjects. CMI was diagnosed on the basis of confirmation of a CTH of at least 5 mm below the foramen magnum by T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). All subjects of the healthy control group underwent brain MRI, and the MRI findings were normal for all of them.

Radiological evaluation

The structures of the brain and skull base were investigated by MRI, using an open 1.5-T magnetic resonance (MR) unit (Magneton Open Viva, Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany). The following sequences were used for imaging the brain and the base of the skull : 1) a localizer sequence of 3 images, consisting of 1 axial, 1 coronal, and 1 sagittal image in the orthogonal plane [repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE)/flip angle, 40/10/40]; 2) axial T2-weighted MR image (TR/TE, 3000.00/121.00 ms; matrix 256×256; field of view, 170 mm; section thickness, 6 mm); 3) coronal T1-weighted MR image (TR/TE, 400.00/7.70 ms; matrix 256×192; field of view, 90 mm; section thickness, 6 mm); and 4) sagittal T1-weighted MR image (TR/TE, 400.00/7.70 ms; matrix 256×192; field of view, 90 mm; section thickness, 5 mm), with study subjects in the supine position.

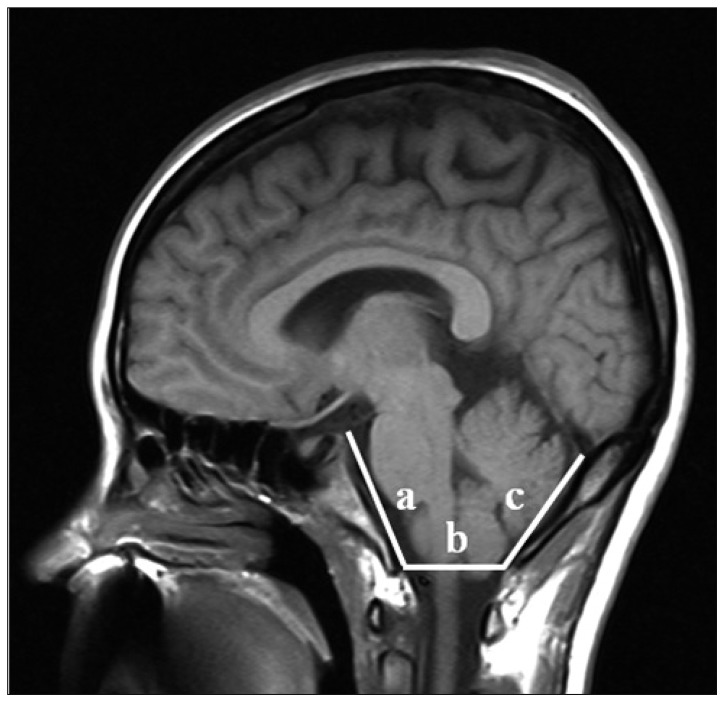

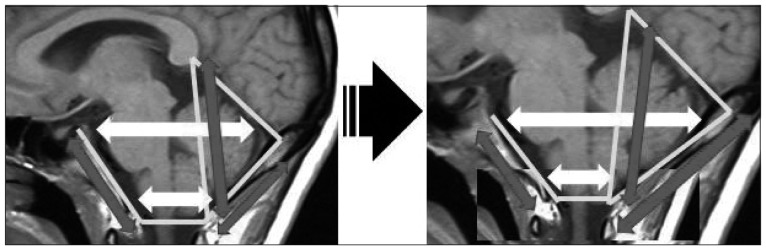

For comparative analysis of morphological differences, we estimated the length of the basiocciput, as determined from the distance of the basioccipital synchondrosis to the basion (a in Fig. 1), the length of the foramen magnum, as measured from the basion to the opisthion (b in Fig. 1), and the length of the supraocciput, as measured from the internal occipital protuberance to the opisthion (c in Fig. 1), on the midline sagittal T1-weighted MR image following to the methods described by Noudel et al.23) To estimate the steepness of clivus, we measured the angle between the clivus and the McRae line (α in Fig. 2), as well as the angle between the supraocciput and the McRae line (β in Fig. 2). The angle between the tentorium and a line connecting the internal occipital protuberance to the opisthion was measured to estimate the steepness of the cerebellar tentorium (γ in Fig. 2) using the same midline sagittal T1-weighted MR images.

Midsagittal T1-weighted MRI shows the posterior cranial fossa, the brainstem and cerebellum. a : length of clivus, b : the anteroposterior length of the foramen magnum from distance between the basion and opisthion on the McRae line, c : the length of the supraocciput between the internal occipital protuberance and the opisthion.

Midsagittal T1-weighted MRI illustrates demonstrating the measurements of three structural angulations. α : angle of clivus, β : angle of the cerebellar tentorium, γ : angle of occipital protuberance.

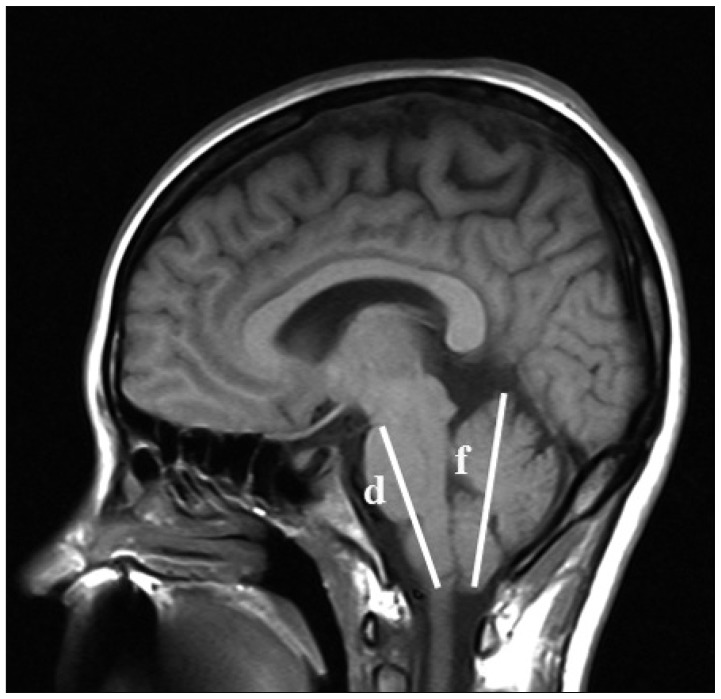

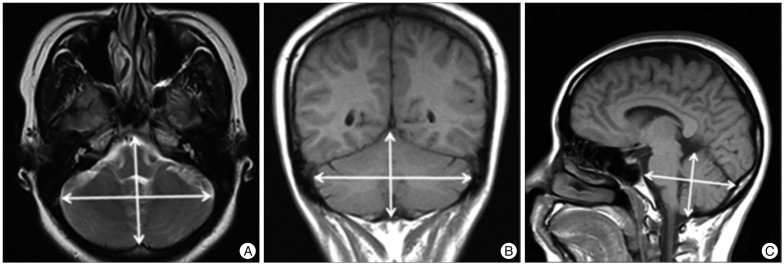

The dimensions of the neural structures were calculated by measuring the length of the brainstem between the midbrain-pons junction and the medullocervical junction, as described by Dagtekin et al.5) (d in Fig. 3), and by measuring the vertical length of the cerebellar hemisphere (f in Fig. 3) from the highest to the lowest point. We measured the superoinferior, anteroposterior, and right-to-left maximum distance of the posterior cranial fossa on axial, coronal, and sagittal midline T2-weighted MR images (Fig. 4).

Midsagittal T1-weighted MRI shows the neural structure of the posterior cranial fossa. d : the length of the hindbrain midbrain-pons junction and the medullocervical junction, f : the vertical length of the tentorium with cerebellum.

Demonstration of linear measurements for the maxium diameters of posterior fossa on T2-weighted MRI. (A) Anteroposterior length and bi-cerebellar length of cerebellum on axial view, (B) supero-inferior length and bi-cerebellar diameter of cerebellum on coronal view, (C) supero-inferior length and anteroposterior length of cerebellum on sagittal view.

Statistical evaluation

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software for Windows (version 12, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The values of all morphometric parameters were compared between the CMI group and the control group using the Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical significance was assessed for p<0.05.

RESULTS

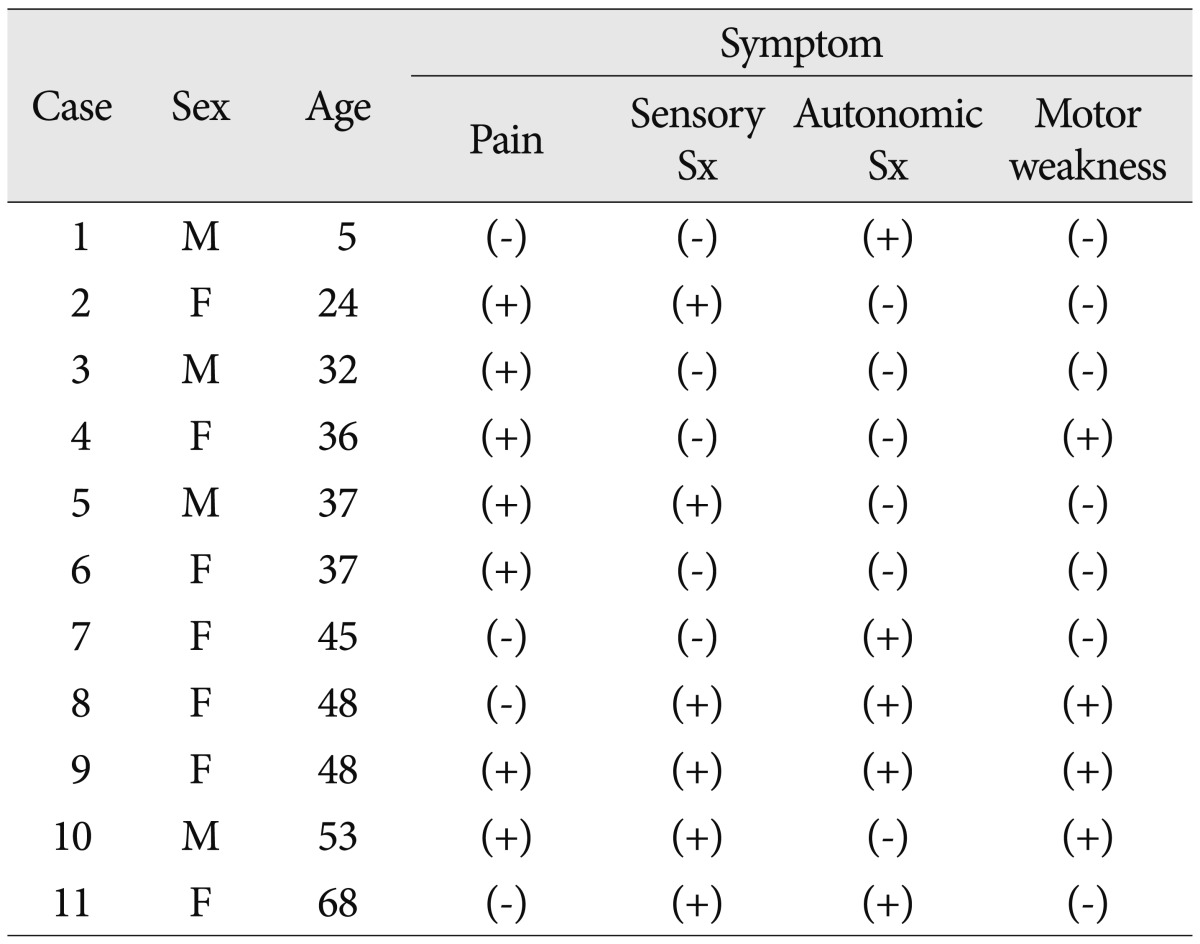

The mean age of patients with CMI was 40.9 years (range 5-68 years, median 28 years), and that of control subjects was 38.8 years (range 6-69 years, median 38.5 years). The main symptoms of patients included sensory changes (7 patients, 58.3%), posterior neck pain (6 patients, 50%), autonomic symptoms (5 patients, 41.7%), and motor weakness (4 patients, 33.3%) (Table 1). For management of patients with CMI, craniectomy with duroplasty (10 patients, 83.4%), craniectomy only (1 patient, 8.3%), or shunts (1 patient, 8.3%) were performed.

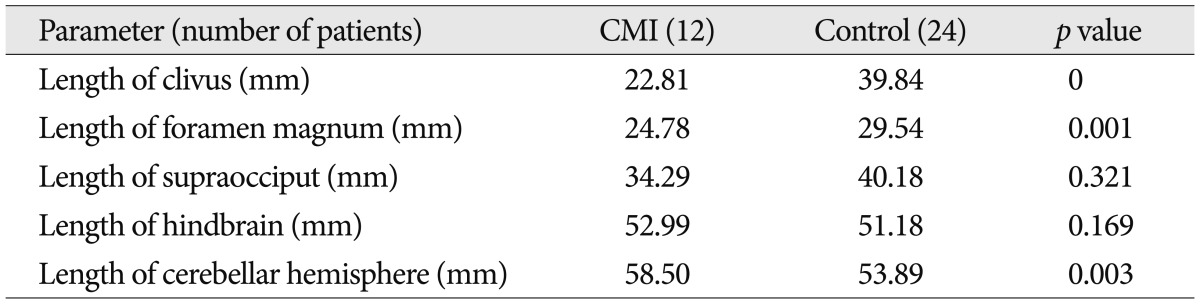

We found that the length of the clivus had significantly decreased in the CMI group (22.81 mm) compared to the control group (39.84 mm) (p=0.000). The mean anteroposterior length of foramen magnum in CMI group (24.78 mm) was shorter than that in the control group (29.54 mm) (p>0.05). The mean length of supraocciput in CMI group (34.29 mm) was shorter than that in the control group (40.18 mm) (p>0.05) (Table 2).

Comparisons in the mean values of the posterior cranial fossa between CMI patients and control group

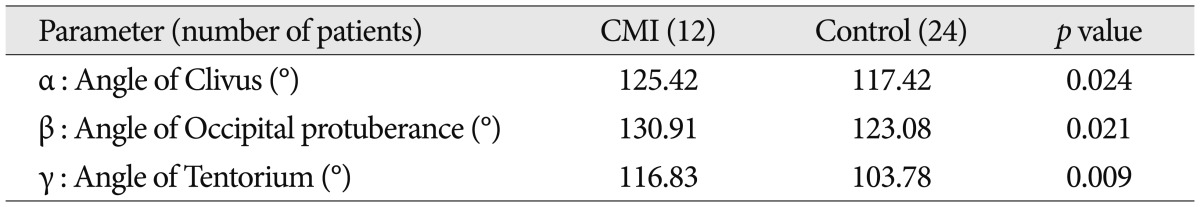

The mean angle of clivus was significant larger in the CMI group (125.42 degree) than that in the control group (117.42 degree) (p=0.024). The mean angle of occipital protuberance was significant larger in the CMI group (130.91 degree) than that in the control group (123.08 degree) (p=0.021). The mean tentorial angle was significant larger in the CMI group (116.83 degree) than that in the control group (103.78 degree) (p=0.009) (Table 3).

Comparisons in the mean values of of three structural angulations between CMI patients and control group

The mean length of brainstem in CMI group (52.99 mm) was longer than that in the control group (51.18 mm) (p>0.05). The mean vertical length of cerebellar hemisphere in CMI group (58.50 mm) was longer than that in the control group (53.89 mm) (p=0.003) (Table 2).

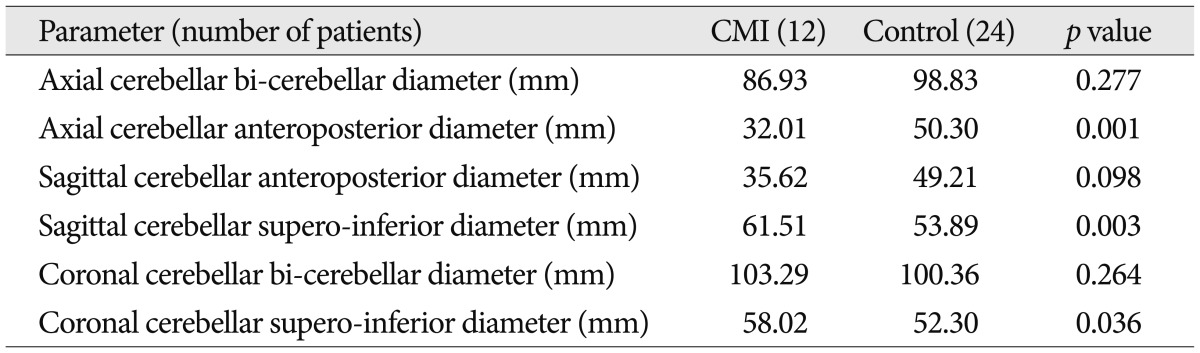

The mean length of axial antero-posterior aspect in cerebellum was significant shorter in the CMI group (32.01 mm) than that in the control group (50.30 mm) (p=0.001). The mean length of coronal supero-inferior aspect in cerebellum was significant longer in the CMI group (58.02 mm) than that in the control group (52.30 mm) (p=0.036). The mean length of sagittal supero-inferior aspect in cerebellum was significant longer in the CMI group (61.51 mm) than that in the control group (53.89 mm) (p=0.003) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

CMI is a congenital disorder involving chronic caudal CTH into the cervical canal, and it is often associated with syringomyelia28). CMI is also known as adult-type Chiari malformation, chronic tonsillar herniation, or hindbrain herniation; CMI narusually presents after the second or third decade of life22). In 50-76% of patients, the malformation is associated with hydromyelic cavitation of the spinal cord and medulla oblongata6). In this study, most patients with CMI were in their third or fourth decade of life, and some patients had syrinx.

In many previous reports, CMI is often related to anomalies of the base of skull, such as basilar invagination, and is less frequently associated with brain abnormalities other than CTH22). CTH is encountered in various etiopathogenic conditions such as global cranial constriction associated with multiple craniosynostosis, acromegaly, achondroplasia, downward traction of the spinal cord associated with tethered cord syndrome, cranial settling and cerebellar ptosis associated with hereditary disorders of the connective tissue, elevated intracranial pressure from the hydrocephalus and space-occupying lesions, intraspinal hypotension with CSF leakage, and lumboperitoneal shunting23). In our study, all patients presented CTH, however, they had normal brain structures without any other congenital malformations.

From an embryological perspective, the foramen magnum consists of cells of 2 different origins. One is the chondrocranium that constitutes the bones at the base of the cranium by endochondral ossification and the other constitutes the parachordal cartilage around the cranial end of the notochord. They fuse into the cartilaginous mass that is derived from the sclerotomal regions of the occipital somites. These cartilaginous masses grow extensively around the cranial end of the spinal cord and contribute to the base of the occipital bone. Finally, these masses form the boundaries of the foramen magnum5). After birth, growth of the cranial base continues at the sphenooccipital synchondrosis until adolescence.

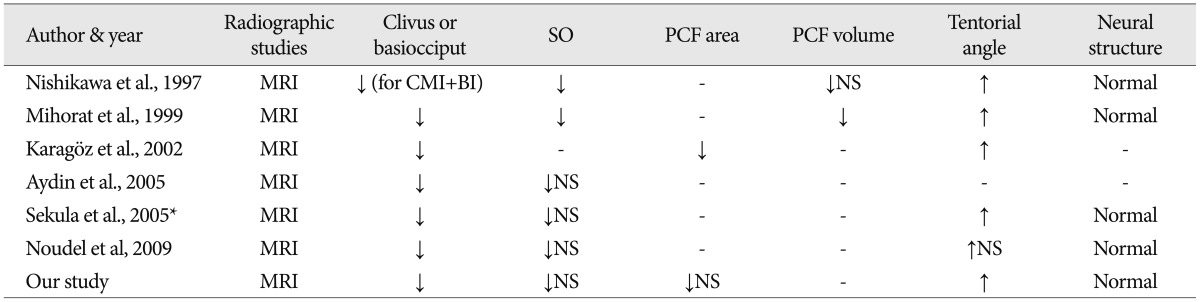

CMI is an accepted result of paraxial mesodermal defect of the parachordal plate or premature stenosis of the sphenooccipital synchondrosis23,27). We agree with this proposed theory, and the results of this study showed similarities to previously reported articles (Table 5). Furthermore, we propose that premature stenosis of the sphenooccipital synchondrosis causes premature closure of the sphenooccipital synchondrosis, similar to craniosynostosis of the calvaria. The shape of the posterior cranial fossa eventually changes into a narrow funnel shape, reflecting the slab-sided and narrow posterior cranial fossa, such as inverted oxycephaly of coronal suture craniosynostosis (Fig. 5). We analyzed many morphological parameters of the posterior skull base and elucidated the transformation into the narrow funnel shape of the posterior cranial fossa.

Schematic illustration of the changes of the posterior cranial fossa in the Chiari malformation type I (CMI) patinets.

For more than one-hundred years, various modalities have been employed to manage CMI decompression. Some authors suggested performing only a simple suboccipital craniectomy with C1 or C1, C2 laminectomy15,21). Others recommend enlargement of the dura of the posterior fossa in addition to the craniectomy2-4,7-14,16-18,20,21). Shindou et al.26) performed foramen magnum decompression with extreme lateral rim resection, followed by dural enlargement was revealed to be the most effective treatment for CMI whether associated with syringomyelia or not. Bilateral resection of the tonsil has been advocated by some surgeons in order to achieve an optimal decompression of the cervico-occipital junction3,8,11,24,30). Our study revealed that posterior cranial fossa transformed to narrow funnel shape. The posterior cranial fossa has a sigmoid sinus as a bilateral limitation and there are no smaller change of the bilateral diameter of the posterior cranial fossa in CMI group. Moreover, anterior-posterior diameter of the foramen magnum showed smaller change in CMI group than control group. For the effective posterior cranial fossa decompression, the sufficient cephalocaudal extension of the craniectomy of the posterior cranial fossa in patients with symptomatic CMI is important.

CONCLUSION

The parameters evaluated in this study suggest an underdeveloped occipital bone in patients with CMI compared with the normally developed hindbrain. We also elucidated the transformation of the posterior cranial fossa into the narrow funnel shape. The sufficient cephalocaudal extension of the craniectomy of the posterior cranial fossa has more decompression effect than other type extension of the craniectomy in CMI patients.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund and Hallym University Medical Center research fund.