Transorbital Penetrating Intracranial Injury by a Chopstick

Article information

Abstract

A 38-year-old man fell from a chair with a chopstick in his hand. The chopstick penetrated his left eye. He noticed pain, swelling, and numbness around his left eye. On physical examination, a linear wound was noted at the medial aspect of the left eyelid. Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) study showed a linear hypodense structure extending from the medial aspect of the left orbit to the occipital bone, suggesting a foreign body. This foreign body was hyperdense relative to normal parenchyma. From a CT scan with 3-dimensional reconstruction, the foreign body was found to be passing through the optic canal into the cranium. The clear plastic chopstick was withdrawn without difficulty. The patient was discharged home 3 weeks after his surgery. A treatment plan for a transorbital penetrating injury should be determined by a multidisciplinary team, with input from neurosurgeons and ophthalmologists.

INTRODUCTION

Transorbital penetrating intracranial injury makes up only a small percentage of all head injuries. However, such injury accounts for nearly one-quarter of penetrating head injury cases in adults, and one-half of the cases in children15). The diagnosis is straightforward when the absence or presence of the foreign body fragment in the wound is confirmed. Yet, diagnosis based on an incomplete history and trivial trauma is difficult and thus, the penetrating injury may be overlooked. Furthermore, patients may not exhibit immediate neurological deficits. Serious events may occur several days, months, or even years after the injury9,14,20,26). We treated a man with orbitocranial penetrating injury caused by a chopstick.

CASE REPORT

While heavily intoxicated, a 38-year-old man fell down from a chair with a chopstick in his hand. He noticed pain, swelling, and numbness around his left eye. On physical examination, a linear wound was noted at the medial aspect of the left eyelid (Fig. 1). Neurologic examination revealed a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15/15. Vision and light reflex in the left eye were lost. Examination of facial nerve revealed facial weakness on the left side. The rest of the cranial nerves were normal. There was no other motor or sensory deficit.

The remarkably swollen left eyelid and a small laceration at upper medial epicanthal area of the left eye are presented.

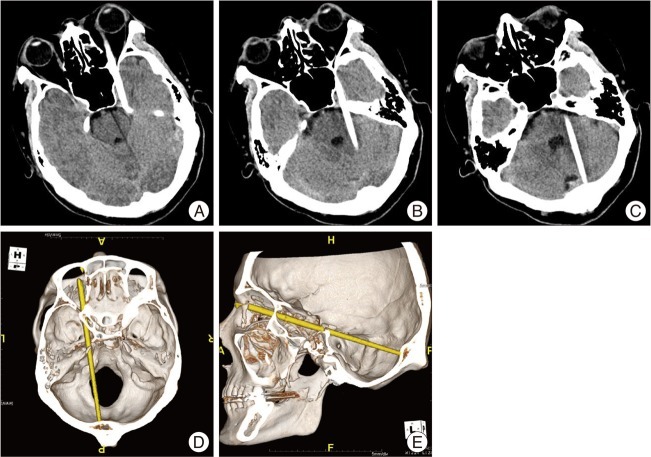

A noncontrast CT study showed a linear hypodense structure extending from the medial aspect of the left orbit to the occipital bone, suggesting a foreign body. This foreign body was hyperdense relative to normal parenchyma. From a CT scan with 3-dimensional reconstruction, we were able to observe the foreign body going through the optic canal into the cranium (Fig. 2). A CT angiogram showed no vascular injury.

A, B and C : A noncontrast CT study shows a linear hyperdense structure extending from the medial aspect of the left orbit to the occipital bone, suggesting a foreign body that was hyperdense relative to normal parenchyma. D and E : A CT scan with 3-dimensional reconstruction shows foreign body going through the optic canal into the cranium.

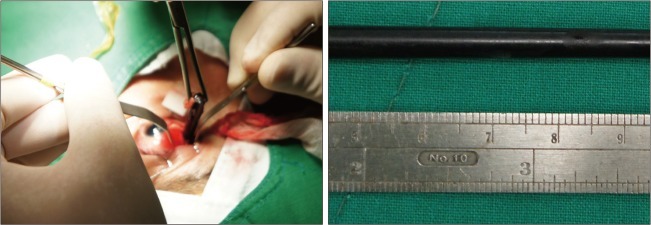

The patient was placed on high-dose steroids for optic nerve protection as well as prophylactic antibiotics. He was taken to the operating room for removal of the chopstick via transorbital approach, conducted jointly by members of the neurosurgery and ophthalmology departments. Clear plastic chopstick was withdrawn without difficulty, and no craniotomy was performed (Fig. 3).

Intraoperative photograph shows the plastic chopstick, at about 14 cm in length. Chopstick was removed surgically.

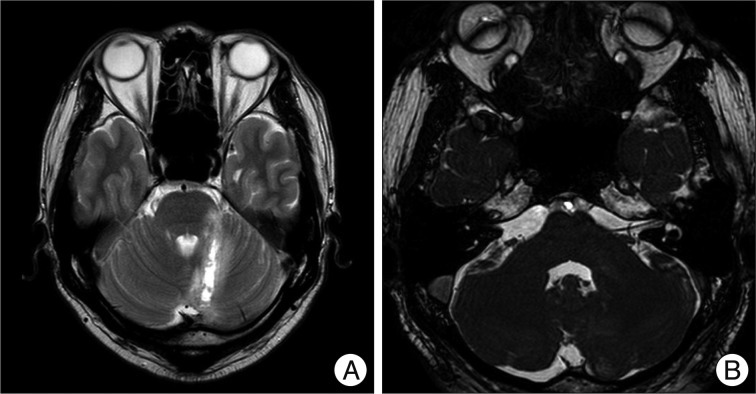

The postoperative course was uncomplicated. Antibiotics were administered for 3 weeks. The patient remained nonreactive to light and facial weakness but was otherwise neurologically intact. On postoperative Day 8, the patient was examined by magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. MR imaging revealed that left cerebellum injuries were not extended from the previous CT scan (Fig. 4A). Constructive Interference in Steady State (CISS) image also revealed no injuries to the left facial nerve (Fig. 4B). The patient was discharged home 3 weeks after his surgery.

DISCUSSION

Transorbital penetrating brain injury by a foreign body is relatively rare. The orbit, which has the shape of a horizontal pyramid on a posteromedially directed axis, tends to deflect objects toward the apex, where the superior orbital fissure or the optic canal may provide passage intracranially11). However, of the two major routes by which foreign bodies penetrate intracranially20,25), the most frequent is via the orbital roof, due to the fragility of the superior orbital plate of the frontal bone. Such penetration often leads to frontal lobe contusion. The second most frequent site of penetration is the superior orbital fissure, through which foreign bodies occasionally reach the brain stem through the cavernous sinus, resulting in a serious injury. A third, rarer avenue of penetration is the optic canal, where the object is directed into the suprasellar cistern, close to the optic nerve and ICA19).

Complete physical examination, including full neurological and ophthalmological examinations, is important in the diagnosis and appropriate treatment of any patient diagnosed with penetrating orbital trauma. All patients, regardless of age, with obvious ocular or palpebral injury should undergo full examination to rule out penetrating intracranial injury4,17). Intracranial trauma cannot be excluded by a benign external appearance21) or by an intact globe16).

Noncontrast CT scanning is the key imaging modality used when intracranial injury is suspected in an orbital trauma in order to determine the course of the object and the extent of bone and parenchymal injury1,8,12,24). MR imaging of the brain is useful in cases of wooden foreign body injury, since dry wood has a similar density to air and hydrated wood has a similar density to the soft tissue on a CT scan, making diagnosis potentially difficult6,18,23). Cerebral angiography, or other less invasive modalities including CT angiography or MR angiography, is indicated when there is evidence of possible vascular injury, either by the location and trajectory of the foreign body or by evidence of hematoma on CT scanning1,7,23). If there is suspicion for vascular injury, angiography should also be performed to evaluate for traumatic aneurysm, which can develop soon after a perforating injury5).

Immediate complications include intracerebral hematoma, cerebral contusion, intraventricular hemorrhage, pneumocephalus, brain stem injury, and cerebrovascular injuries3,9,13,22). If the foreign body is retained in the orbit and cranium, severe infectious complications may occur later10). When a patient develops a cerebral abscess postoperatively, a retained foreign body should be ruled out2).

Early radical debridement and removal of the retained fragment are mandatory to prevent potentially fatal infectious complications11). Depending on the location of the fragment, a transorbital or transcranial approach can be selected. Postoperative intensive antibiotic treatment should be administered to prevent late infectious events.

CONCLUSION

Transorbital penetrating intracranial injuries are uncommon and therefore, the management of such injuries is often complex. However, since neuroimaging examinations, including CT and MR imaging, are widely available and early diagnosis is also possible, early surgical exploration will most likely result in success. A treatment plan for transorbital penetrating injury should be determined by a multidisciplinary team, with input from neurosurgeons, otolaryngologists, and ophthalmologists.