INTRODUCTION

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage may commonly occur during spinal surgeries and it may cause dural tears12,1516,19). These tears may result in hemorrhage in the entire compartments of the brain.

There are many risks related to this complication. One of the most gruelling complication is remote hemorrhages which can develop in any compartments of the brain4,910,1920). Most of the reported hemorrhages are from the veins located in the cerebellar region1,23,45,68,910,1214). Moreover, pneumocephalus and/or pneumorrhachis in the upper segments of the spine can rarely occur after CSF leakage.

We report a case of hemorrhage mimicking aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and concurrent pneumocephalus due to CSF leakage following lumbar spinal surgery. The possible mechanisms of action for this unusual complication is also discussed.

CASE REPORT

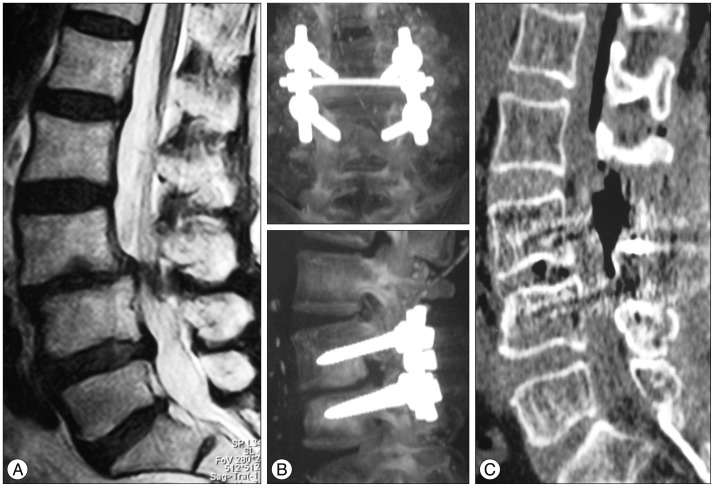

A 70 year-old woman with the history of controlled hypertension was admitted with the complaints of neurologic claudication and low back pain. Neurological examination was uneventful. Imaging studies revealed degenerative spondylolisthesis and spinal stenosis at L3-4 (Fig. 1A). The patients underwent decompressive laminectomy and an excessive CSF leakage was occured after an accidental dural tear during posterior instrumentation (Fig. 1B, C). The tear was sutured primarily and a suction drain was inserted prior to the closure of the skin. The patient awoke in good neurological status however approximately 100 cc of hemorrhagic fluid was drained in the first 12 postoperative hours. Consecutively, the patient deteriorated and had focal seizures. Computed tomography of the brain showed sylvian-periinsular subarachnoid hemorrhage and pneumocephalus in the right cerebral hemisphere (Fig. 2A, B). Cerebral angiography was performed in order to exclude an underlying aneurysmal pathology, which did not reveal any vascular abnormality (Fig. 2C).

The patient was treated conservatively. Computed tomography angiography was repeated 4 weeks after the operation which demonstrated normal vascular findings. The patient was discharged in a good condition with full mobility and no neurologic deficit has been detected through the 4 year follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Cerebellum is the most commonly site of remote hemorrhage during supratentorial, infratentorial and spinal surgery4,910,1215,1920). Although the exact pathophysiology of these hemorrhages is unknown, recent reports suggest that it is from the venous origin9). Several suggestions to explain the mechanism such as excessive loss of CSF due to intraoperative aspiration or drainage with infratentorial venous stretching and rupture secondary to downward cerebellar herniation, impaired venous drainage in case of intraoperative head rotation with obstruction of one jugular vein, increased transmural venous pressure dependent on loss of CSF volume, coagulation abnormalities, episodes of arterial hypertension and neoplastic angiomas have been reported1,45,917,1920).

Supratentorial hemorrhage after spinal surgery is a very rare entity. Nonetheless, only a few cases of supratentorial and infratentorial intraparenchymal hemorrhage secondary to intracranial hypotension following spinal surgery has been reported in the English literature2,514,1920). In these cases, headache and signs of cerebellar dysfunction were the prominent symptoms14,1920), whereas only one case presented with seizure2). Although previously reported intraparenchymal hemorrhages were in different sizes, shapes and locations, none of them were located in the right periinsular-sylvian cistern and mimicked aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. This "pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage" phenomenon has been reported in anoxic-ischemic encephalopathy with brain swelling, venous sinus thrombosis, subdural hematoma and intracranial hypotension13). Engorgement of the superficial veins secondary to elevated intracranial pressure and severe brain edema manifesting as hypoattenuated parenchyma is the mechanism blamed for pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage7,13). Brain sagging in conditions that causes intracranial hypotension narrows the subarachnoid spaces, displaces CSF, compresses the basal cistern and sylvian fissure and consequently results in brain edema. These neurological changes can be observed as hyperdensity of the anterior and middle cerebral arteries as well as obliteration of the basal cisterns on computed tomography13). CSF leakage during surgery may trigger the abovementioned mechanism, which may explain the pathophysiological process in our case.

On the other hand there are other reported mechanisms to explain remote intraparenchymal hemorrhage19). One of the most widely accepted hypothesis is the rupture of blood vessels due to intracranial hypotension and consequent increase in transluminal venous pressure9). Another possible mechanism is downward sagging of the cerebellum that causes stretching and occlusion of bridging cerebellar veins with subsequent hemorrhagic venous infarction6). The previously reported cases2,1419,20) suggested that, movement of the brain due to intracranial hypotension from massive CSF loss can cause acute occlusion of multiple infra- and supratentorial bridging veins. This would explain the presence of multiple foci of intraparenchymal hemorrhages seen in the entire brain tissue. It is reported that, alleviation in CSF pressure causes augmentation in the carotid flow velocity, especially in patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus18). In addition to the pathophysiology of pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage, these suggestions could also help to explain the mechaniam of action. Otherwise, it is accepted that older people constitute the majority of patients who undergo spinal surgery and are much more vulnerable to the occurrence of intracranial hemorrhage after CSF leakage in association with a history of underlying chronic hypertension and age-related brain atrophy11).

In the light of the relevant literature, we believe that the pattern of this confusing subarachnoid hemorrhage seems to be originating from both venous and arterial vasculature of the brain. Although our patient complained of headache, neurological deterioration of mental status and seizures, which can also be symptoms of hemorrhage in an aneurysmatic origin, cerebral angiography and control computed tomography showed no vascular pathology.

CONCLUSION

Increase of carotid blood flow velocity as a result of CSF leakage and brain edema related alterations in CSF pressure can cause pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage. Mimicking an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, in clinical symptoms and radiologic findings makes this case interesting and extraordinary. This rare complication must be considered in conditions with unexplained neurological deterioration, after CSF leakage during spinal surgery, in older patients especially with chronic hypertension and brain atrophy.