INTRODUCTION

An acute subdural hematoma (SDH) is regarded as a complication of a head injury, and bleeding is commonly associated with laceration of the bridging vein in the subdural space. However, acute SDH, without any history of trauma, are uncommonly reported. Acute spontaneous SDH due to ruptured cortical artery aneurysm is very rare, and only 3 cases of it have been reported2,4,8). We experienced a case of acute spontaneous SDH with contrast media extravasation from cortical artery that was demonstrated on angiograms. The bleeding focus was pathologically proved to be an aneurysmal artery.

CASE REPORT

A 58-year-old male patient developed sudden onset headache and right hemiparesis. The patient was drowsy mentality on admission. He had no history of head trauma. The coagulation profile was normal.

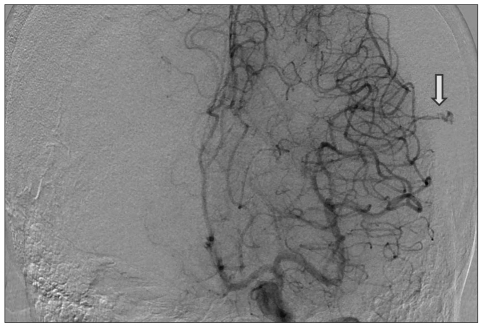

Brain computed tomography scan demonstrated acute SDH along left cerebral convexity with mild midline sift (Fig. 1A). There were no associated brain contusions or subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebral angiography was performed and revealed a localized extravasation of the contrast media from distal cortical MCA branch. No other vascular abnormality responsible for the acute SDH lesion was found (Fig. 2). After angiography, the patient deteriorated to comatose mentality. On neurological examination, Glasgow Coma Scale was 6, light reflex of both pupil was no response. Brain CT showed increase of thickness of hematoma and shifting of midline structures (Fig. 1B). Decompressive craniectomy for removal of SDH was performed.

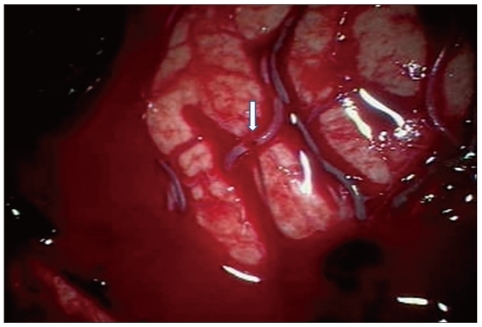

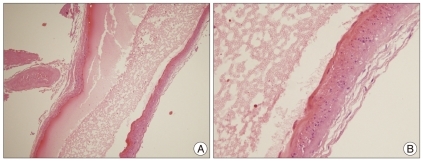

At operation, we evacuated the subdural clotted blood and found bleeding point at a cortical middle cerebral artery located near the sylvian fissure. There was a small round hole at the cortical artery, which projected out through the arachnoid and the bleeding directly spouted into the subdural space (Fig. 3). We controlled the bleeding with electrocoagulation and diseased artery was excised for pathology. Histological examination of the arterial wall revealed thinning of tunica media and degenerative change of tunica intima. There was no atherosclerotic or inflammatory change. The histological diagnosis was aneurysmal artery (Fig. 4).

He showed progressive improvement and had mild hemiparesis at the time of discharge.

DISCUSSION

There are numerous nontraumatic conditions that may result in an acute SDH either as a result of direct bleeding into the subdural space or as an extension from an intracerebral hemorrhage : ruptured intracranial aneurysms, ruptured cortical artery, hypertensive cerebral hemorrhage, neoplasms, hematologic disorders, anticoagulant and thrombolytic therapy, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, dural arteriovenous fistulas, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome1).

Since the first report by Munro7) in 1934, many cases of spon taneous SDH have been reported and cortical branch laceration was thought to be a principal causative factor. Several authors have reported mechanisms of the formation of this acute SDH. Vance10) found that acute SDH was caused by rupture of cortical arteries. In his autopsies, small twigs connecting to the dura mater were identified that branched perpendicularly from the cortical arteries. These twigs were torn by the shearing force present in head injury, bleeding occurred, and acute SDH was formed. According to Drake's report3), there were adhesions between the dura mater and cortical arteries. Laceration of the adhesive arterial wall was caused even by trivial trauma, resulting in bleeding. The points of rupture were always located at branches in the territory of the middle cerebral artery, since middle cerebral arteries branch into many arteries and supply a wide territory of the cerebral hemisphere. Tallala and McKissock9) reported the causative mechanism of rupture of arteries was based on connection between the dura mater and arteries. According to him, the preceding head injury forms subdural clots, and adhesions of the dura and the cortex of the brain involving the cortical arteries are formed. The involved artery is lacerated by friction force and bleeding occurs. McDermott et al.6) described the presence of a rete mirable connecting a cortical artery and the dura mater, and found that the disruption of this connection by trauma caused acute SDH.

The incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with an acute SDH due to ruptured intracranial aneurysms varies from 0.5% to 7.9%2), but a pure SDH without subarachnoid hemorrhage due to ruptured aneurysm is extremely rare. There are only 3 cases involved in ruptured distal middle cerebral artery aneurysm2,4,8). Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the occurrence of acute SDH after aneurysm rupture. Previous minor hemorrhages may fix an aneurysm to local arachnoid adhesions, resulting in bleeding directly into the subdural space when an arachnoid tear occurs after aneurysm rupture5). A second mechanism may be due to a hemorrhage under high pressure, leading to pia arachnoid rupture and extravasation of blood into the subdural space5).

In the present case, we found bleeding through a hole in the arterial wall without any arachnoid adhesion in the operative field. Histological diagnosis of the artery was aneurysmal artery. We thought the round shape hole was considered as the site of ruptured small cortical aneurysm. But, we could not found the real ruptured small cortical aneurysm.

An extravasation of contrast media from a cortical artery is usually noted in the late arterial phase. This is a useful finding for diagnosing this disease and localizing the bleeding point. If contrast media extravasation is shown, the bleeding point is apparent and a craniotomy of an appropriate size can be done. If preoperative angiography does not demonstrate extravasation and the bone flap is not large enough, persistent bleeding into the field may require a bone flap to be extended from where the bleeding seemed to be coming. To prevent this situation, craniotomy should be sufficiently large over the sylvian fissure to enable the source of bleeding to be controlled.

The choice of initial neuroradiological investigation in patients with spontaneous pure acute subdural hematoma should be based on the neurological status of the patient. If the patient presents with a stable neurological condition, angiography should be performed prior to surgery to dictate the best strategy. In the presence of an aneurysm or an arteriovenous malformation, the patient should undergo emergency surgery to evacuate the hematoma and obliterate or extirpate the lesion. If the angiography does not demonstrate the source of bleeding, the patient can be managed conservatively or surgically according to the subsequent evolution of the neurological status. If necessary, additional investigation with contrast enhanced CT or MRI can be performed to rule out dural tumors.

In cases of patients presenting with rapid neurological deterioration, immediate decompression surgery should be performed before performing angiography. In the absence of intraoperative identification of a cortical arterial rupture or other source of bleeding, complementary post-operative arteriography is required.

CONCLUSION

We report a rare case of acute spontaneous SDH that showed contrast media extravasation from cortical artery on angiograms. Patient with spontaneous acute SDH should ungergo angiography to seek the cause of bleeding. However, even when no vascular abnormality is recognized, the possibility of angiographically unvisualized lesion should be considered, and during operation, the brain surface beneath the hematoma should be carefully examined.