INTRODUCTION

Unidentified dural tear that results in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage is a potential complication during spinal operations. The likelihood of this issue increases as the complexity of the procedures increases, especially for revision surgery11). Although most cases of dural injury do not cause intracranial hemorrhage, however, some patients may experience this type of complication.

Intracranial hypotension created by CSF leakage through a durotomy site is considered the main pathogenic mechanism of intracranial hemorrhage5,13). Various treatment options for both intracranial hemorrhage and durotomy site exist and can be individualized to the patient. The present paper reports a rare case of acute intracranial subdural hemorrhage and intraventricular hemorrhage that resulted from CSF leakage through an unidentified durotomy site during spinal revision surgery combined with preexisting asymptomatic chronic subdural hemorrhage. The intracranial hemorrhages and dural injury site were successfully treated with burr hole drainage alone. Therefore, considerations in the treatment of unidentified durotomy associated with intracranial hemorrhage after spinal surgery are presented.

CASE REPORT

Examination

A 69-year-old female with a history of previous spinal surgery was diagnosed with progressively worsening neurogenic claudication. The patient had no history of head injury and had not taken antiplatelet or anticoagulant medications. Spinal magnetic resonance imaging showed severe spinal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis from level L2 to S1.

Operation

The patient underwent decompressive laminectomies and lumbosacral arthrodesis at the corresponding levels. During the operation, dural injury and CSF leakage in the surgical field were not evident.

Postoperative course

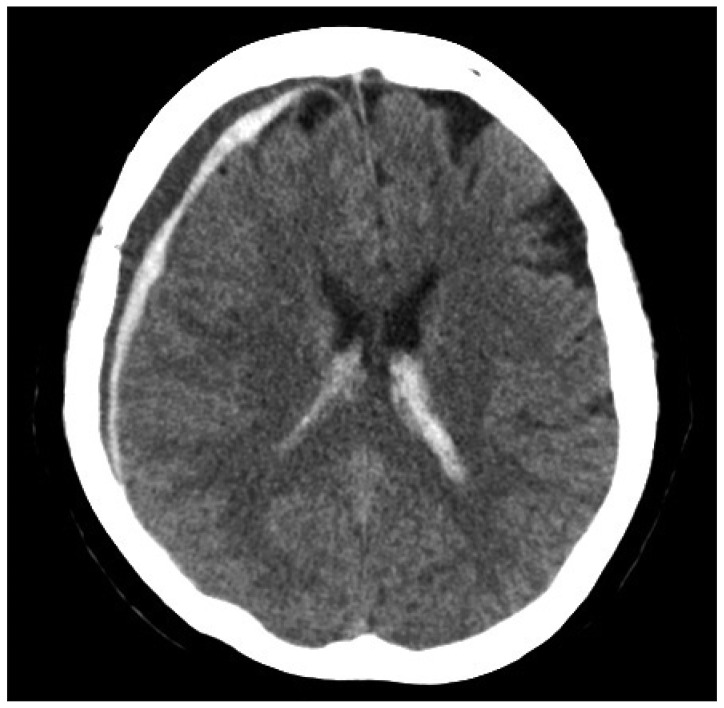

The patient was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit for hemodynamic monitoring after surgery. On the first postoperative day, approximately 940 cc of serosanguineous fluid was collected from two subfascial wound drains. She complained of severe headache and had one episode of generalized tonic clonic convulsion. An emergent brain computed tomography (CT) scan showed acute and chronic subdural hemorrhages along the right frontal, temporal and parietal lobes, with a maximal width of 1.5 cm, 5 mm right-to-left midline shift, and intraventricular hemorrhage in both lateral ventricles (Fig. 1). After the CT scan, her mental status recovered, and she presented no focal neurological deficits.

Intracranial hypotension caused by CSF leakage through an unidentified dural injury site unlikely resulted in acute subdural hemorrhage and intraventricular hemorrhage at the preexisting asymptomatic chronic subdural hemorrhage. On the third postoperative day, one burr hole was made over the right parietal skull under local anesthesia. The brown colored chronic subdural hemorrhage was gushed out and a catheter was positioned in the subdural space. A daily average of approximately 228 cc of blood-containing CSF was drained for 7 days. Serosanguineous fluid from the spinal subfascial wound drains markedly decreased, and the drain was removed 2 days after cranial CSF drainage. The catheter was maintained for 5 more days, and the patient recovered without further complications.

DISCUSSION

Incidental durotomy during spinal surgery is a frequent complication for spinal surgeons. The reported prevalence ranges widely from 0.67% to 17.4%14,15). Immediate diagnosis and primary repair for incidental durotomy at the time of surgery does not affect postoperative clinical outcomes7), but unidentified durotomy that results in continuous CSF leakage can lead to fatal neurosurgical emergencies. The incidence of durotomy that is clinically significant and not identified at the time of surgery has been reported to be 0.28%3). The majority of these patients report postural headache. Some patients, however, may experience intracranial hemorrhage complications, such as epidural, subdural, intraventricular, and cerebellar hemorrhage with manifested signs of neurological deterioration6,8,12,16). Secondary intracranial hypotension has been suggested to be a pathogenic mechanism of intracranial hemorrhage5,13). Iatrogenic CSF leakage causes pressure differences between the intracranial and spinal compartments. The resultant brain sagging toward the skull base stretches and tears the venous structure of the brain and can cause certain types of intracranial hemorrhage, such as subdural or cerebellar hemorrhage.

Zimmerman and Kebaish16) reported four cases of intracranial hemorrhage after primary repair of incidental durotomy and stated an inability to identify consistent etiologic factors and difficulty in the urgent diagnosis of intracranial hemorrhage because of nonspecific symptoms that are commonly manifested in older patients. Older people constitute the majority of patients who undergo spinal surgery, and their brain condition is more susceptible to the occurrence of intracranial subdural hemorrhage compared with younger patients1). Our case also presented acute subdural and intraventricular hemorrhage, in addition to the incidental finding of asymptomatic chronic subdural hemorrhage without any history of antiplatelet medication or trauma. Older patients may then be considered more susceptible to the occurrence of intracranial hemorrhage after iatrogenic spinal CSF leakage.

Although rare, the possibly devastating course of this complication suggests that more diagnostic and therapeutic considerations may be needed after the diagnosis of unidentified or delayed dural injury that results in intracranial hemorrhage.

Various treatment options mentioned in previous reports2,4,9,10) exist, but they must be applied after evaluation of intracranial abnormalities using brain imaging modalities. Primary repair with various sealing materials may be a more reliable method but less effective with regard to its invasiveness and morbidity associated with revision surgery under general anesthesia. Non-operative methods, including bed rest, epidural blood patch, and spinal subarachnoid CSF drainage, may be selected as main or ancillary treatment components. Spinal subarachnoid CSF drainage without information about intracranial hemorrhage9) could be more dangerous and may exacerbate the pressure gradient between the intracranial and spinal compartments, leading to enlarge the intracranial hemorrhage.

Cranial subarachnoid CSF drainage has similar mechanism of treatment to its spinal counterpart. However, it has not mentioned in previous articles because of its invasiveness and limitation in general use. Although in particular cases, if the drainage or craniotomy for intracranial hemorrhage resulting from intracranial hypotension is needed, the positioning of a catheter for subsequent cranial CSF drainage could be another treatment option to seal off the spinal dural injury site without secondary intention.

CONCLUSION

Intracranial hemorrhage resulting from secondary intracranial hypotension associated with unidentified dural injury after spinal surgery is a rare complication. Brain imaging studies to evaluate intracranial abnormalities are essential in the planning of treatment options for the dural injury site. Cranial subarachnoid CSF drainage could be a treatment option for closure of spinal dural tear site in particular case when cranial CSF drainage is possible.