INTRODUCTION

Spinal subarachnoid hematoma (SSH) is a rare pathology that can cause cauda equina syndrome or spinal cord compression. Trauma, lumbar puncture and coagulopathy are the main causes of SSH. Additionally, vascular malformations and spinal tumors have also been reported to cause SSH1,2,3). In rare cases, SSH can spread into the intracranial subarachnoid space because of its connection to each other3,4,7,8,10,11,13). However, severe cerebral vasospasm has rarely been reported as a complication of intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) from SSH3). Here, we report an extremely rare case of SSH with intracranial SAH, which caused severe cerebral vasospasm and profound neurological sequelae.

CASE REPORT

A 67-year-old woman with a history of hypertension was admitted to our hospital with acute chest pain. Under the diagnosis of unstable angina, anticoagulant and dual antiplatelet therapy was initiated with intravenous heparin (25000/IU), aspirin (75 mg/day), and clopidogrel (75 mg/day). Laboratory tests showed a partial thrombin time of 58.3 seconds and a prothrombin time of 11.6 seconds with an international normalized ratio of 13.24. One day after commencing anticoagulant therapy, she developed sudden severe back pain and paraplegia (Grade I/V).

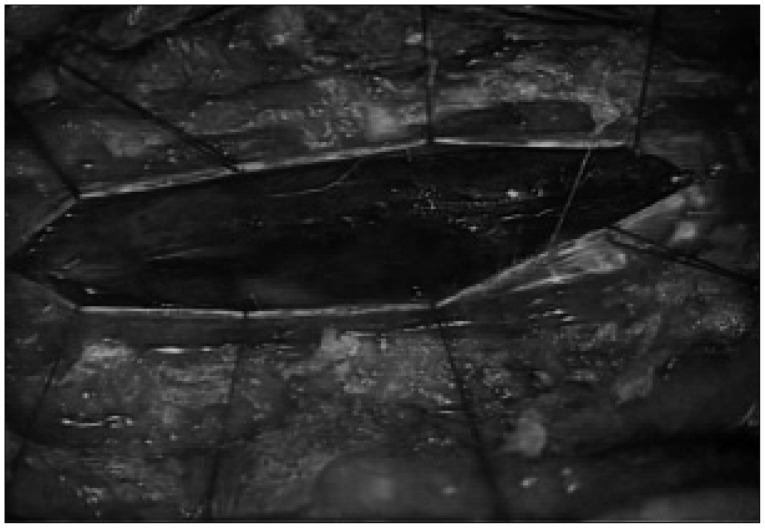

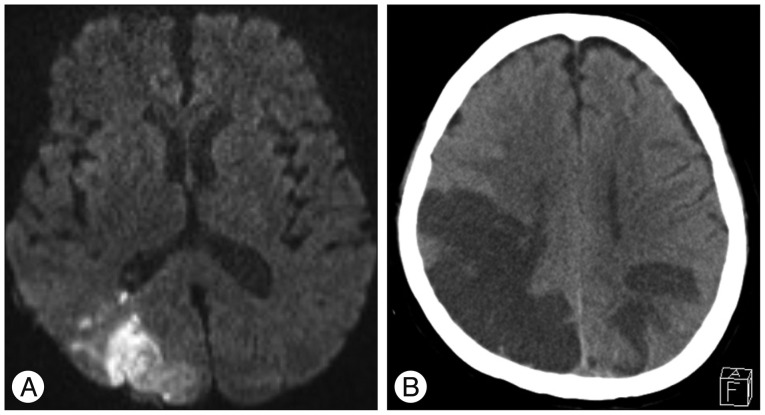

Although she also had hypoesthesia below the T2 dermatome, her consciousness was completely normal. Thoracic T2-weighted MRI showed intradural extramedullary low signal intensity at the T2-3, which was consistent with spinal subarachnoid hematomas. High signal intensity was also observed from C5 toT4 in the spinal cord (Fig. 1). Surgical exploration was then undertaken to decompress the spinal cord. Prior to the operation, heparinization was reversed and antiplatelet administration was discontinued. With total laminectomy at T1-4, we could not find any hematoma in the subdural space. However, thick hematoma compressing the spinal cord was found beneath the arachnoid membrane (Fig. 2). The hematoma extended into the anterior, upper and lower subarachnoid space around the spinal cord. Much of the hematoma was removed sufficiently and the spinal cord became soft. Postoperative MRI demonstrated reduced spinal cord edema. The next day, the patient complained of a severe headache and brain CT revealed SAH on both parietal lobes (Fig. 3). For prevention of vasospasm, nimodipine was administered to prevent cerebral vasospasm intravenously. Hypervolemic and hypertensive treatments were not started because of her poor heart function. Nevertheless, her consciousness decreased over time and blurred vision developed with hemiplegia seven days after surgery. Brain CT and MRI revealed multiple cerebral infarctions in the right posterior cerebral artery territory, left parietal lobe and right watershed area (Fig. 4). Conventional cerebral angiography showed diffuse severe vasospasm of the intracranial arteries, which was most prominent in the right middle cerebral artery and temporo-occipital branches. Perfusion defects were also noted in the bilateral parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes on perfusion CT scan (Fig. 5). After one month of intensive care, she was referred to the rehabilitation department. After six months, she displayed partial improvement of right lower extremity motion, cognition and vision. However, there was no improvement of weakness in her left extremities.

DISCUSSION

Spinal hematoma can be classified as epidural, intradural, subarachnoid, or intramedullary. Of these pathologies, SSH is rare and its radiological diagnosis is extremely difficult. In the majority of previous cases, SSH was diagnosed on the basis of surgical or autopsy findings. Domeniccuci et al.2) found that the identification of the subarachnoidal location of the hematoma, which is surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and separated from the internal dura mater surface, is the only way to diagnose SSH with CT and MRI.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to distinguish SSH from subdural hematoma. In addition, SSH frequently has a disastrous outcome with an overall mortality of 17.4% in patients with surgical intervention2). Furthermore, poor general condition and concomitant diseases are responsible for high mortality in patients with SSH. Although extremely rare, simultaneous intracranial SAH and SSH can occur because of the connection of the subarachnoid space. In 1956, Henson and Croft5) first reported a case of a SSH with blood-stained CSF within the cranium at autopsy. Since then, totally 10 cases of SSH with symptomatic cranial SAH have been reported on the basis of CT finding (Table 1)3,4,7,8,9,10,11,13).

The main causes of SSH are lumbar puncture and anticoagulant. In particular, arterial injuries after a lumbar puncture or anticoagulant administration may cause extensive bleeding, which could result in the spreading of hematoma into the intracranial subarachnoid space7,8,9,13). Although intracranial SAH and SSH could occur independently, the mechanism appears to involve the extension of SSH into the intracranial arachnoid space. Consequently, cerebral symptoms, such as, headache or a decreased consciousness could occur several hours to days after spinal symptoms. In this case, the cerebral symptoms followed the spinal symptom. In addition, there was no any vascular abnormality on cerebral angiography. Additionally, the SAH was dominant on dependent portion of both parieto-occipital lobes with no SAH in basal cistern. Furthermore, the reversal of anticoagulant was performed before spinal operation. Thus, the authors confirmed that the extension of spinal hematoma into intracranial subarachnoid space is the cause of intracranial SAH.

Fisher CT grades of cranial SAH vary from 2 (SAH <1 mm thick) to 4 (SAH with intra-ventricular hemorrhage or parenchymal extension) in the reported SSH cases. The symptoms and signs of SSH range from back pain to complete paraplegia. Cranial symptoms and signs also vary widely from headache to comatose state. In particular, patients with bleeding from the segmental artery can immediately fall into deep coma following a lumbar puncture.

Among the previously reported cases, decompressive laminectomy and SSH removal was performed in one cases. Embolization of the spinal segmental artery was performed in two cases. Emergent ventricular drainage was performed in two patients with intraventricular hemorrhage. Four patients were treated conservatively, even though three of them died because of cardiac and pulmonary complications. Half of survivors had poor outcomes with permanent neurological sequelae regardless of treatment method.

Cerebral vasospasm is a common complication and occurs in about 70% of cases after SAH due to aneurysmal rupture6). On the contrary, SAH from vascular malformation or brain tumor rarely causes vasospasm12). Specifically, cerebral vasospasm due to SAH extending from SSH has rarely been reported. Espinosa-Aguilar et al.3) described symptomatic vasospasm due to SAH extending from SSH. They confirmed the vasospasm by transcranial Doppler ultrasonography and cerebral angiography. Consciousness was fully recovered in their patient. However, no case of SAH associated with SSH causing multiple cerebral infarctions and delayed neurological sequelae, has been previously reported. In our case, cerebral vasospasm was severe and multiple cerebral infarctions developed in the dominant region of the SAH. Thus, left hemiplegia and visual disturbance eventually remained despite an improvement in right leg mobility. The extension of thick SAH due to copious spinal bleeding, promoted by anticoagulant therapy, was the cause of the severe symptomatic vasospasm in the current case. In addition, preventive measure for vasospasm was limited because of poor heart function, which led to aggravated neurological sequela. Thus, we suggest active preventative treatment for vasospasm, even in cases of SAH extension from SSH, because vasospasm can give rise to additional neurological sequela and poor clinical outcomes.

CONCLUSION

We report an extremely rare case of intracranial SAH causing severe vasospasm and cerebral infraction from SSH. This specific case developed after the initiation of anticoagulant therapy. Although rare, SSH can extend into the intracranial subarachnoid space and cause severe vasospasm. Therefore, spine surgeons should be aware of the possibility of simultaneous intracranial SAH after an intraspinal hemorrhage. They should monitor brain CT findings and neurological status carefully. If intracranial SAH is detected, surgeons should anticipate possible delayed neurological complications due to cerebral vasospasm.